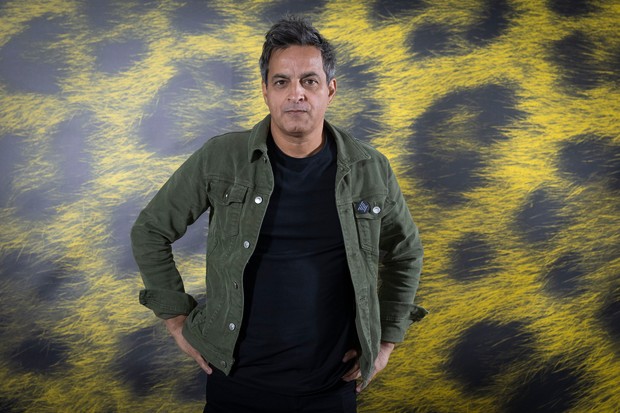

Sylvain George • Director de Nuit obscure — au revoir ici, n’importe où

"Durante la noche, las reglas no existen"

por Marta Bałaga

- El director francés se adentra en la oscuridad en su película sobre un grupo de chicos marroquíes que sueñan con llegar a Europa mientras están bloqueados en Melilla

Este artículo está disponible en inglés.

Awarded a Special Mention in the Locarno Film Festival competition (see the news), Sylvain George’s black-and-white film Obscure Night – Goodbye Here, Anywhere [+lee también:

crítica

tráiler

entrevista: Sylvain George

ficha de la película] shows a group of kids from Morocco, dreaming of escaping to Europe yet still stuck in Melilla. Mistreated and lonely, they form a little family of their own, taking over the city at night.

Cineuropa: You pose important questions in the film, but weren’t you afraid you would alienate viewers just because of its running time?

Sylvain George: When I start working, I have a few ideas, but it’s necessary for things to change later on. It’s so important to be open like that. Whether I can achieve that in three seconds or 23 hours makes no difference to me. I don’t believe that we have to submit to one fixed format. Lav Diaz, who was also in Locarno’s competition this year, does that, too: if he feels he has to make a three-hour film, he does so. But if it needs to last ten hours instead, it’s not a problem.

I didn’t want to make a film about “refugees”: I tried to understand how immigration policies work and how European countries make these agreements. I started in Calais [in May They Rest in Revolt (Figures of Wars)], and now I have moved to Melilla, but it’s always about trying to understand the consequences. I needed time to understand the pace of these kids’ lives, to show how their day starts and how it ends. They call them arrāga, or “those who burn”. They burn their ID cards, they “burn the sea”. I didn’t want to look down on them, ever. We all know films where people like them are shown as victims. You watch them, cry a little and feel better about yourself.

What sets Obscure Night apart from “those films” is a lot playfulness. These boys aren’t complaining; they just go about their day.

When they hide food and clothes in the sewers, it’s another consequence of these policies I just mentioned. But they have found a way to deconstruct them; it’s a game. They have been hurt, even beaten, but sometimes they just want to play – with the police, with the authorities. We have this saying, la porte joue sur ses gonds [lit. “the door ‘plays’ on its hinges]. They prove it’s actually possible: it’s possible to open the world to something new. This film can be harsh sometimes, but yes, there is joy.

Many stories about immigrants focus on their journey: “How did you get here? What happened?” You are certainly not pushing that.

I thought it would be more interesting to express things via images. I didn’t want to make a documentary based on teary testimonies – I wouldn’t even know how to do that. Also, these boys don’t really talk about their past. They are focusing on the present, on fighting, on friendships. It was important to respect that. When two of them got very close, that’s when they started to talk.

During the transit, they don’t speak a lot either. It takes up so much of your energy – some of them take drugs to survive that. One of them was a victim of sexual abuse, but he would never tell his friends that. A bit later, when their situation becomes more stable, all of these memories come back, and things get violent: they self-mutilate or lose the will to live. They start to understand what really happened to them. I would never force them to share that.

Because you don’t do that, it’s easy to forget you are there. Was it hard to blend in like that?

I wasn’t making a film about them. The idea was to discover this reality with them. For me, time is really the key. If you spend time with your protagonists, that spawns intimacy. Recently, I was accused of making a film about “wild” children, but it’s this system and this town’s colonial past that put them in that position, not me.

While watching it, something felt odd, and I realised it was because in my mind, the night doesn’t belong to children. But that’s when they take over the city.

They can make it their own; they can jump fences. In that sense, night is political. Their gestures change, and it’s so quiet. Nobody is screaming at them. I don’t show that many interactions with the locals, and some of them give them food or clothes every once in a while, but these meetings can also be violent. At night, the rules don’t apply.

¿Te ha gustado este artículo? Suscríbete a nuestra newsletter y recibe más artículos como este directamente en tu email.