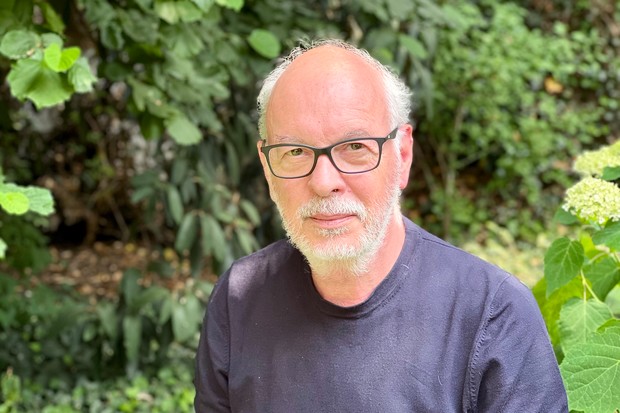

Philippe Van Leeuw • Director of The Wall

"I wanted to make a modern western"

- The Belgian filmmaker spoke to us about his new movie, which paints an uncompromising portrait of a young female police officer on the border between Mexico and the USA

After focusing on the story of war-torn Rwanda in The Day God Walked Away [+see also:

film review

trailer

film profile], and then the more topical subject of the Syrian conflict in In Syria [+see also:

film review

trailer

interview: Philippe Van Leeuw

film profile], Philippe Van Leeuw is back with The Wall [+see also:

film review

interview: Philippe Van Leeuw

film profile], an uncompromising portrait of a young female police officer on the border between Mexico and the USA who’s powered by a now-uncontrollable racist rage. The film is screening in BRIFF’s National Competition.

Cineuropa: How would you describe the film in a few words?

Philippe Van Leeuw: It’s the portrait of a woman who knows no limits, who’s lost in a way of thinking that Trumpism has really brought to light. She’s leading a battle, like some kind of Jean d’Arc who’s gearing up to save America. At a certain point, she kills someone who can’t defend themselves. But because she wears a uniform and has sworn an oath, she feels strong. And, a bit like Trump, whatever happens she thinks she’ll get away with it.

What was the spark that lit the fire for this project?

Trump coming to power! I’m always writing. I’ve got other projects like this one, which are there, ready and waiting. And then, when you finally finish one, you just want to make something totally different. But, out of nowhere, I wanted to make a modern western featuring a sheriff and American Indians. So I started looking for American Indians, and I came across this American Indian nation whose land straddles the border between Mexico and the USA. These people, who have been there for millennia, witnessed a barrier being built right in front of their home.

Secondly, I’d made two films about a victim suffering at the hands of a torturer. I wanted to explore that dark character this time round, find out who he was, how he ended up there, but I didn’t want to do it in a chaotic war space where anything goes and where rules no longer apply. On the contrary, I wanted it to exist because of rules.

Jessica’s character is die-hard, but she’s also in a really fragile, existential place. Her only unshakeable conviction is racism. I think it’s one of the only "dogmas" which there’s no going back from. Once you’re racist, you’re racist forever. She’s also a character who struggles every day, who’s moving around in a massively chauvinist, professional environment and who suffers humiliations and insults. She’s consumed by such rage. And such loneliness. She’s someone who excludes herself from social interactions. I think she feels sure of herself by not comparing herself to others.

But she meets someone who makes her question all that…

The American-Indian character played by Mike Wilson belongs to a thousand-year-old lineage, he represents a kind of knowledge, culture, and negation of that culture which has been at work ever since America became "American", if I can say that. But that doesn’t stop Jessica from thinking that her word, as a "real" American, is worth more than his, despite the fact that he was there thousands of years before she was.

The fate reserved for migrants on the American border resonates with situations which are currently playing out all over the world, like with that boat, recently, in the Aegean Sea.

In order to make this film, I collected lots of first-hand accounts, and what came out of them were the incredible journeys people make, trips on foot across mountains of mud to reach the American border. Especially since today, such crossings are definitive, or near enough. Before, migrants came to work in California; they’d come for the harvest and then return home to add a new section to their house. There was an exchange between their work and the economy, which worked for Mexico and the USA, but which no longer works at all. In Europe, we’re forever closing ourselves off, too. Pervading fascism in our countries makes us view these people as a burden, when they’re actually contributing towards the economy. We can’t carry on this way indefinitely. I’m convinced that if we opened our borders, there’d be inflows and moments of crisis but there’d also be outflows, because everyone wants to go home in the end. People don’t leave their homes unless they absolutely have to. That was something I explored in my previous film too.

(Translated from French)

Did you enjoy reading this article? Please subscribe to our newsletter to receive more stories like this directly in your inbox.